By: Sophie Bellenis, OTD, OTR/L

Occupational Therapist; Community-Based Skills Coach

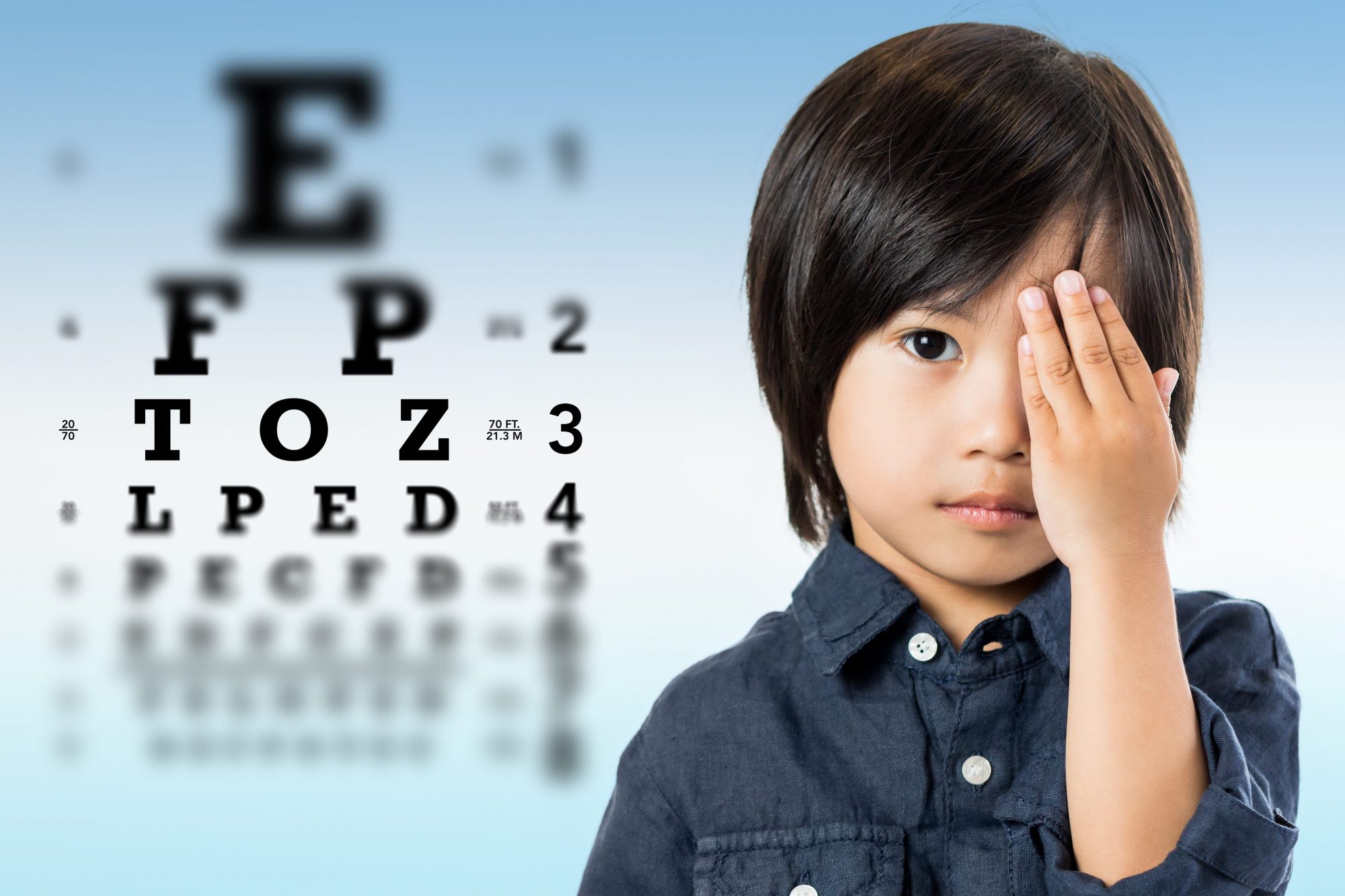

When a school nurse pulls a child into his or her office to complete a basic eye screening, he or she may write, “20/20 vision in both eyes. No visual concerns.” This child has successfully looked at an eye chart and read the letters; demonstrated the ability to look straight ahead, from an appropriate distance without things becoming blurry or illegible; and demonstrated visual acuity, or the ability to see with acceptable clarity.

But does this necessarily mean there are no concerns?

Visual acuity measures whether a stimulus is being seen – not necessarily if the information is truly being understood. The visual system is a complex part of the central nervous systems that incorporates the eyes, ocular pathways and brain to produce and interpret sight. It requires consistent communication between all of these individual anatomical pieces, the vestibular system and the skeletomuscular system. Essentially, vision is complicated and messy and requires many many different skills.

Breaking It Down

In terms of visual skills needed for academic success, we often break things down into three main areas: ocular motor control, visual perception and visual motor integration.

- Ocular motor control describes the ability to physically move the eyes using the 9 ocular muscles. It encompasses the ability to track an object across a screen or a line of text across a book, or the ability to look up at the board and then quickly refocus on a sheet on paper on the desk. Imagine trying to watch a basketball game without the ability to track the ball across the screen smoothly. It quickly becomes tiring and frustrating. Occupational therapists often refer to these specific eye movements with technical terms, such as visual saccades, pursuits, convergence/divergence and accommodation. But in essence they describe eye movement.

- Visual perception or visual processing is in many ways more nuanced. It focuses on the brain’s ability to organize, interpret and fully understand the information it receives from the eyes. Two main skills needed at school are visual figure ground and visual closure.

- Visual figure ground is the ability to discern relevant information from a busy or cluttered background. A student with visual figure ground difficulty may not be able to search a busy white board and find a homework assignment. These students may also be visually overwhelmed by a worksheet with 20 math problems, but successful with the same problems presented individually.

- Visual closure is a skill that specifically helps with reading efficiency and fluency. It is the ability to identify or visualize a complete form or picture when given incomplete visual information or when only a small piece of the image is shown. Visual closure allows us to read a sentence quickly without stopping to decode each individual letter. It is aslo oen raeosn taht mnay pelope can raed setneces wtih julmbled up ltetres. We recognize the form, not simply the sequential letters. : )

- Visual closure plays a role in sight words and reading partially-covered papers or street signs in the community. While there are many more important visual perception skills, these two examples have functional, measurable effects in the classroom setting and are commonly identified through occupational therapy testing.

- Visual motor integration (VMI) describes the ability to use all of these foundational visual skills in conjunction with foundational motor skills. It is the ability to interpret visual information and produce a precise motor response. In the classroom, this affects a student’s ability to copy shapes, produce legible handwriting and use scissors to cut along a line. Not only can these things be difficult, they can be exhausting as a child tries to use all of these skills at once.

While all of these visual components have multiple layers and intricacies, it is important to simply acknowledge that there’s more than the eye can see when it comes to vision. A child who “can’t see the board,” but has 20/20 vision, may just be visually overwhelmed. A child who looks at a page full of small block text and immediately gives up may not have the visual skill to read across a line. And a child who is learning to read beautifully, but still has difficult forming the letters in his name may have poor visual motor integration. Fortunately, there are many interventions and accommodations that can help build on and develop these skills further to foster confidence and success in the class and community.

About the Author:

Neuropsychology & Education Services for Children & Adolescents (NESCA) is a pediatric neuropsychology practice and integrative treatment center with offices in Newton, Massachusetts, Plainville, Massachusetts, and Londonderry, New Hampshire, serving clients from preschool through young adulthood and their families. For more information, please email info@nesca-newton.com or call 617-658-9800.

(or adolescent or adult) is developing skills at a rate and capacity commensurate with their age and ability level. In order to do this in an efficient, equitable, and consistent manner, test developers identify skills they think are important in learning, devise a task that appears to quantifiably measure that skill, give that task to children in different age groups and then transform the raw scores attained by the children into a common scale. This allows them to compare different children within an age group, and this also allows them to compare the same child at different ages. Some common measurement scales are standard scores, scaled scores, Z scores, T-scores and percentiles. All of these formats are based on a normal distribution (remember the bell curve?) in which the majority of scores fall within a certain area with increasingly fewer scores falling at either end. The “bump” where most scores fall is described as average (between 25th and 75th%ile) with the tails receiving an above or below average description. While these descriptions do not begin to capture the whole child, they do convey information about how a child is performing relative to developmental expectations based on what we know about children of the same age. They can also tell us if the child is making age expected progress according to their unique learning curve. Furthermore, most people are good at some things and not so good at others, and the pattern of their scores can often give us valuable information about their learning profile.

(or adolescent or adult) is developing skills at a rate and capacity commensurate with their age and ability level. In order to do this in an efficient, equitable, and consistent manner, test developers identify skills they think are important in learning, devise a task that appears to quantifiably measure that skill, give that task to children in different age groups and then transform the raw scores attained by the children into a common scale. This allows them to compare different children within an age group, and this also allows them to compare the same child at different ages. Some common measurement scales are standard scores, scaled scores, Z scores, T-scores and percentiles. All of these formats are based on a normal distribution (remember the bell curve?) in which the majority of scores fall within a certain area with increasingly fewer scores falling at either end. The “bump” where most scores fall is described as average (between 25th and 75th%ile) with the tails receiving an above or below average description. While these descriptions do not begin to capture the whole child, they do convey information about how a child is performing relative to developmental expectations based on what we know about children of the same age. They can also tell us if the child is making age expected progress according to their unique learning curve. Furthermore, most people are good at some things and not so good at others, and the pattern of their scores can often give us valuable information about their learning profile. Formerly an adolescent and family therapist,

Formerly an adolescent and family therapist,

By:

By:

Formerly an adolescent and family therapist,

Formerly an adolescent and family therapist,

Connect with Us